With the New Zealand Government in the early stages of designing an offshore wind licensing regime, we review the comparable framework in Australia and look at the lessons that can be learned from New Zealand’s existing offshore licensing regimes. We also explore the potential areas of focus for legislation currently expected to be in force by the latter part of 2024, from licensing application requirements to decommissioning.

Australia’s offshore licensing regime

What can New Zealand learn from the Australian approach? Late last year, the Australian Government enacted the Offshore Electricity Infrastructure Act 2021 (OEI Act), a legislative framework to enable offshore infrastructure projects in Australian Commonwealth waters.

The Australian legislation is a purpose-built regime to regulate offshore renewables developments, and will be a useful analogue for the New Zealand regulators seeking to develop a regime fit for purpose in a New Zealand context.

The newly enacted Australian regime has already seen tangible steps taken forward, with the Australian Government moving late last week to start the process to declare Australia’s first offshore wind zone off the Gippsland coast in Victoria’s south east, with five other offshore areas to follow.

The OEI Act provides for several different types of licences to be granted to potential developers of offshore wind and other renewables projects.

- Declared areas: The Minister for Energy may designate ‘declared areas’ in the waters off Australia. These are intended to plan where offshore generation projects will occur. Feasibility licences, commercial licences and research and demonstration licences are to be granted within the declared areas.

- Feasibility licences: These enable the licence holder to assess the feasibility of an offshore infrastructure project and apply for a commercial licence for the project. Feasibility licences remain in force for seven years (with the possibility of extension).

- Commercial licences: These are applied for by the holder of a feasibility licence (who has the exclusive right to do so). They permit the licence holder to carry out a commercial project for the purposes of exploiting renewable energy resources. Commercial licences remain in force for 40 years, with the possibility of extension.

- Transmission and infrastructure licences: These authorise the licence holder to store, transmit or convey electricity or a renewable energy product. The term of a transmission and infrastructure licence is determined by the Minister.

- Research and demonstration licences: These authorise research into and demonstration of offshore renewable energy infrastructure or offshore electricity transmission infrastructure over the short term.

This regime will serve the dual purposes of allowing the Australian Government the ability to plan and coordinate the development of offshore renewables projects as well as giving potential developers and investors the certainty and time, by way of a statutory licence, to investigate, plan and consent offshore renewables projects. The OEI Act is intended to operate in conjunction with, rather than usurp or replace, all other Commonwealth and State environmental and other requirements.

Merit criteria for granting licences

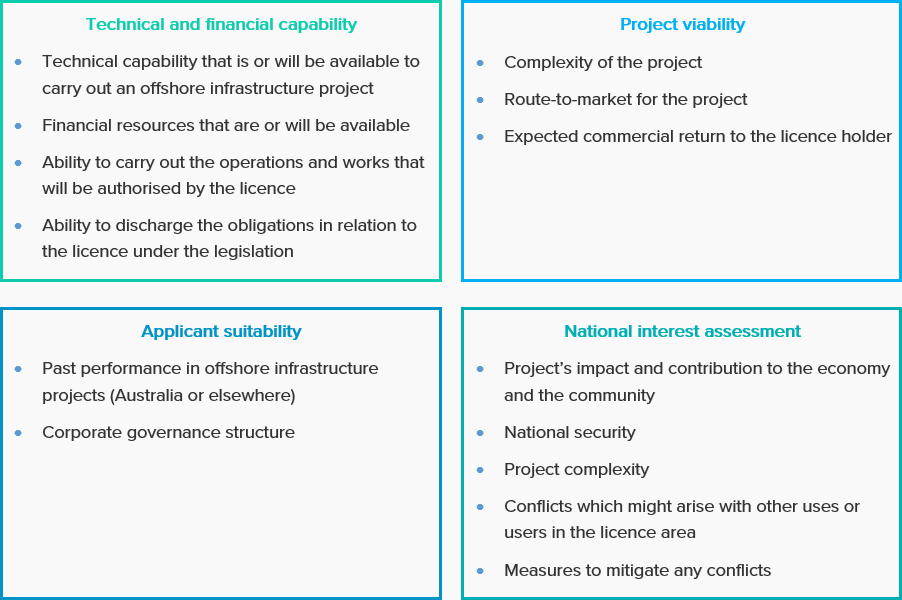

The OEI Act specifies various merit criteria which are to be considered when assessing and determining licence applications. The Minister also has a wide discretionary ability to assess other matters considered to be relevant. The legislation does not provide guidance as to the relative weighting of the merit criteria.

There are four broad categories:

New Zealand considerations

It is not yet known what approach the New Zealand regulators will take to the development of the offshore licensing arrangements for renewables (and, although broader than just wind, we expect offshore wind will be an important focus).

The OEI Act was developed based on existing offshore licensing regimes in Australia, and it is a reasonable assumption that the New Zealand regime will have regard to the approach recently adopted in Australia.

We would also expect the government to consider the existing petroleum regime in New Zealand as well as past practice in terms of how it has been applied – the Crown Minerals Act has been in force for 30 years and provides a robust and ‘road-tested’ licensing regime for the assessment, planning, development and operation of large scale commercial projects in New Zealand offshore waters.

So what do we expect will be some of the key focus areas in New Zealand?

- Financial and technical information and assessment: A key consideration for any applicant and the Crown will be the technical and financial capability of the licence applicant – no doubt detailed information on both of these aspects will need to be provided and assessed (with potentially differing requirements at different phases of the licensing).

- Transfer and change of control requirements: We would expect the legislation to contain a regime enabling licences (or interest in licences) to be transferred between industry participants as well as some form of regulation of changes of control of licensees. This has always been a key focus under the Crown Minerals Act (and more so recently), so we would expect it to be addressed in any offshore wind licensing regime.

- Decommissioning: Requirements to decommission offshore infrastructure as well is its timing, planning and costs will be addressed in the new regime. While the decommissioning activity itself may be many decades away, recent experience would suggest this is not something that will be left to be addressed at that point.

- Ongoing financial capacity assessment: An open question is to what extent the Crown will require the ability, over a project life that could span several decades, to monitor and assess the financial capability and capacity of the licence holder.

- Information confidentiality: One thing the Crown Minerals Act provides for is the confidentiality of commercially sensitive project information that applicants and licensees provide to the Crown in the context of their activities. This is something we expect will need to be addressed as part of developing a commercially robust and appropriately balanced licensing regime.

- Integration with existing regimes: Any new project will require consents and approvals under existing exclusive economic zone and/or resource management legislation (both of which themselves are likely to be reformed). A forward looking approach to integrating all three regimes in terms of the consenting and licensing timeframes and processes would be advantageous.

The commercial and development opportunities associated with offshore wind have been well canvassed, so the hope and expectation will be that a robust commercially workable regime can be put in place quickly to facilitate these projects.

If you have any questions about the matters raised in this article please get in touch with the contacts listed or your usual Bell Gully adviser.